Bioprinting Humans: How Close Are We to the Science of Mickey 17?

3D printing has long been the stuff of science fantasy and the object of Hollywood’s interests, and recent blockbuster Mickey 17 is the latest flick to explore the tech.

The futuristic drama from director Bong Joon Ho sees the titular Mickey (played by Robert Pattinson) join a space colony in 2054 as an Expendable worker. These workers are employed to do the grunt work, and when this labour results in fatality, their bodies are recycled, reprinted, and mentally restored with the memories collected from the original person.

Watching the movie, you can’t help but wonder about the premise’s feasibility- is a bioprinter like this possible? How much of the body could we additively reproduce? Which technologies would we use to bioprint key bodily organs?

Obviously, we are far from the cloning capabilities possessed by the scientists of (evil) expedition leader Kenneth Marshall, yet the film provokes an intriguing thought experiment that serves to illustrate the staggering power of current bioprinting technology.

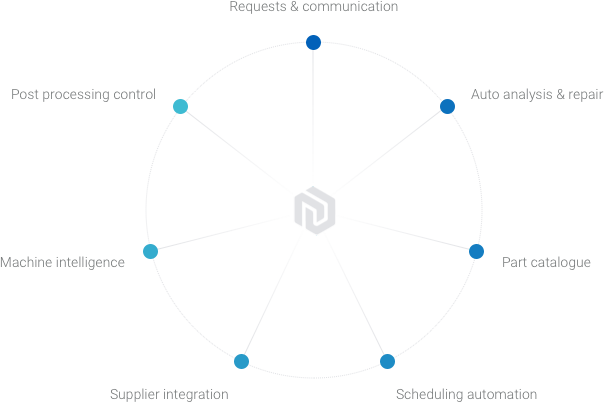

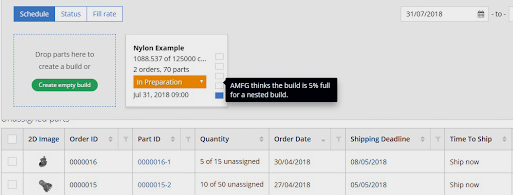

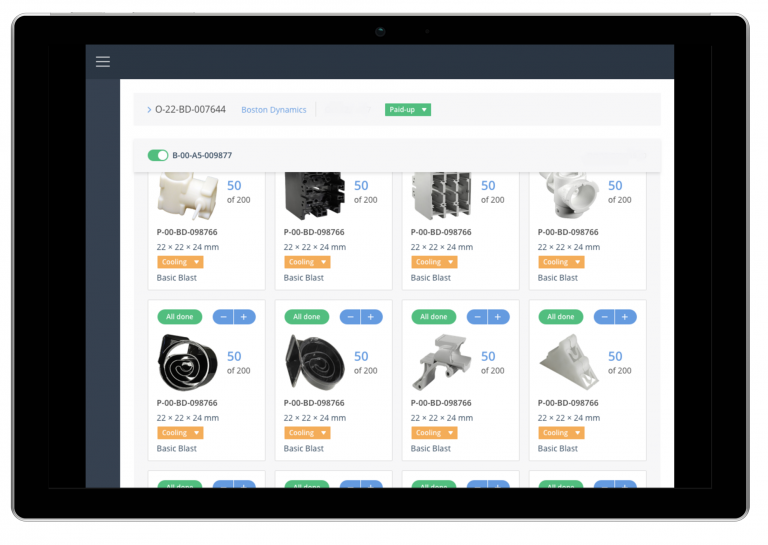

The medical industry is rapidly adopting 3D printing as a production process, from bespoke devices like prosthetics, to life-saving organ implants. AMFG streamlines workflows for companies involved in discrete manufacturing, in the medical industry and beyond, collaborating with companies like HP, Ricoh, and Photocentric to ensure productivity, accuracy, and credibility.

Blast off to planet Niflheim with us, and read on to discover the bioprinting tech catching Hollywood’s eye.

Printing people

3D printing in space has left the domain of fiction; to take just one example, researchers from the University of Glasgow were recently successful in testing a system designed to work in the microgravity of space. Instead of sending items into space, risking destruction and damage when going into orbit, additive manufacturing (AM) fabricators could be placed into space to build structures on demand.

Assuming that the Niflheim colonists could print in space, how would they go about fabricating a human?

In the movie, scientists use waste matter from previous iterations of the people fulfilling the Expendable job role, feeding it through a machine with a stop-start movement that mimics a paper printer.

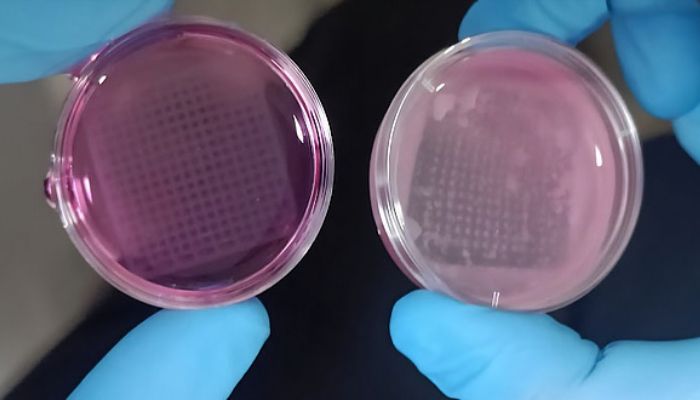

Cell information from the original Mickey would be taken in order to produce bioinks; hydrogel materials which support the cell while they produce their own natural extracellular matrix. Using the patient’s own cells means that there would be no risk of rejection.

3D bioprinting of tissue and organs. Image courtesy of Merck

Creating key organs

The key organs would have to be fabricated first: let’s zoom in on bioprinting tech for the brain, heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys.

Swedish firm Cellink use bioinks that contain real human cells to produce tissues for transplantable human organs, selling these bioinks on to researchers. One such group from Tel Aviv University produced the world’s first bioprinted human heart, replete with cells, blood, vessels, ventricles and chambers.

Lung bioprinting is a technology in its infancy, yet there are promising signs for development. United Therapeutics, together with 3D Systems, have produced a human lung scaffold, the world’s most complex 3D-printed object. The designs consisted of a record 44 trillion voxels that lay out 4000 km of pulmonary capillaries and 200 million alveoli. Moving forward, the two companies hope to celluralise the scaffolds with a patient’s stem cells to create tolerable, transplantable human lungs.

Human vasculature model created using 3D Systems’ Print to Perfusion process. Image courtesy of United Therapeutics

Moving down the body, progress is being made in bioprinting livers and kidneys. Although transplantable, 3D printed versions of these organs are currently impossible, 3D printing has been leveraged to facilitate transplantation. As far back as 2016, surgeons at NHS Guy’s and St Thomas’ used a 3D printed model to produce models of a father and young daughter’s kidneys in order to plan the operation and minimise risks. The transplant was successful.

Producing functional liver tissues is a complex challenge, given that the process would require replicating the organ’s intricate structure and function, including its cardiovascular system. USCD engineers were able to produce a structure that has access to blood supply, is made up of three different types of tissue, and which boasts a production time of mere seconds. Yet manufacturing of the complexity of what would be needed to regenerate an organ (and a person) is still beyond the scope of current bioprinting.

3D printing a functioning, full-sized brain is a feat still fettered by scientific impossibilities, yet this is not to say that significant progress has not been made.

Engineers have printed smaller, simplified brain tissue through producing neural cells and supporting cells, thus creating layered constructs which mimic parts of the cerebral cortex. Scientists at Oxford University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison developed methods to print brain tissue able to communicate and interact with other cells, mimicking the aspects of brain function.

This is still a far cry from the constant shared memories between all iterations of Mickey 17’s protagonist, but the potential implications of this technology may be unprecedented.

Filling in the gaps

Although these five crucial organs are important, it takes more than that to build a human.

No body can exist without a skeleton– Danish company Ossiform proclaim their ability to ‘print bone’. Using a material that mimics natural bone, they develop custom 3D printed bone implants designed to integrate with a patient’s own tissue and eventually be replaced by real bone.

Bioceramic implants are also a promising technology under development. Ceramics that come close to mimicking bone could replace metal and polymer implants.

In regards to the body’s largest organ, a team of researchers from India have created a 3D-printed skin that imitates the human model and designed for tolerance studies (instead of using animals). The imitation skin has a three-layer tissue structure and also uses hydrogels.

3D-printed structure of the skin with human keratinocytes. Image courtesy of Graz University of Technology and the Vellore Institute of Technology (VIT)

3D Systems have recently announced the world’s first MDR-compliant 3D printed facial implant. The patient-specific PEEK implant was used in a maxillofacial reconstruction surgery earlier this year. An EU-funded Keratoprinter project could fill in the gaps; the initiative would create full-thickness, curved human corneas, and aims to restore vision using natural biomaterials such as collagen.

Scientists at MIT have applied a new technique to artificial muscle tissue that contracts in multiple directions and mimics the movements of natural muscles. The new process, acronymised as ‘STAMP’, uses 3D-printed stamps to structure microscopic grooves directly in natural hydrogels, and these grooves subsequently guide the muscle cells as they grow to ensure that they align into functional fibres able to contract in different directions.

Conclusion 17

If we have the same goals as the scientists in Mickey 17, we’re not quite there yet.

However, this thought experiment is a brilliant way to demonstrate the bioprinting capabilities currently available. Obviously, the scope is different and there are lots of practical and regulatory barriers to overcome in the real world, but the companies are offering innovations on a constant basis that promise real world implications.

Organ donation is low, and replacement lists are long. 3D printing has the potential to change lives, and O&P companies are realising this and subsequently implementing solutions.

AMFG’s manufacturing execution system (MES) is the go-to solution for manufacturers of O&P devices.

With open APIs for 3D scanners, market-leading integrations and end-to-end traceability for ISO 13485 compliance, AMFG is at the forefront of O&P Additive Manufacturing.

Chat with one of our experts to learn more: Book a demo

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)