3D Printing in the Maritime Industry: A Comprehensive Guide

Additive manufacturing is setting sail for the maritime industry.

3D printing technology has revolutionised verticals across discrete manufacturing industries, and the next sector commencing adopting additive at an increasing rate is maritime.

Humans have utilised the sea for over 40,000 years, and now companies are turning to AM in an effort to improve production efficiency, reduce costs, and enhance the performance and sustainability of all things maritime- be they boats, vessels, or even surfboards.

Any part for a sea-faring vehicle must be strong, durable, and resistant to a cocktail of environmental challenges, including saline water and UV rays.

Companies are developing 3D printing maritime parts that meet these requirements of hydrodynamics and durability, whilst also wasting less, benefitting from greater design flexibility, and combatting supply chain blocks.

In this article, AMFG navigates the technology behind the wave of popularity that 3D printing is experiencing in this industry, and the reasons behind the choices to adopt further. We have a look at the companies advancing maritime AM at a rate of knots, from surfboards made of recycled algae, to entirely 3D printed boats.

Read on! It’s plain sailing from here…

The technology behind maritime AM

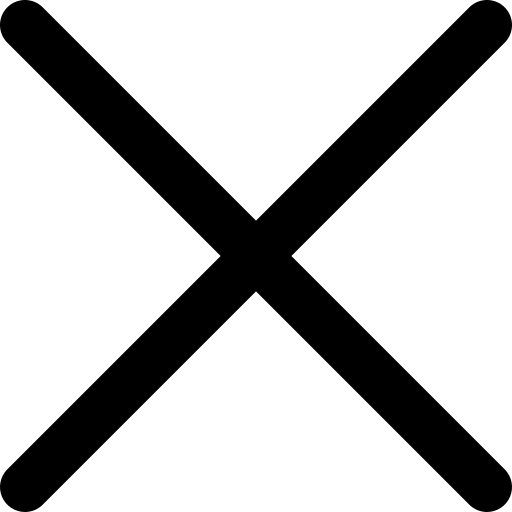

The 3D printed WAAMpeller. Image courtesy of RAMLAB / Port of Rotterdam / Materia

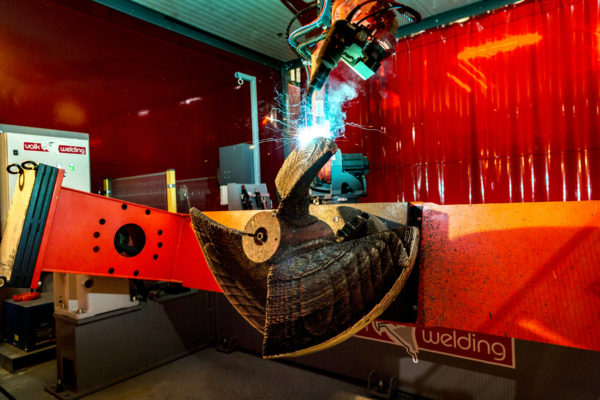

AM is used to create a wide variety of parts in the maritime industry, including hull components, propellers, rudders, spare parts, and even entire structural assemblies. The materials used can range from polymers and composites to advanced metals like titanium, stainless steel, and aluminum alloys, each chosen based on application-specific performance and environmental factors.

Any material used in maritime part production needs to be light, capable of withstanding heavy impacts without damage, not absorb water, be naturally resistant to marine growth, equally distribute weight, and possess a degree of resistance to corrosion and UV.

Several 3D printing techniques are utilised when printing parts, including MJF, FDM, SLS, and WAAM. FDM is the dominant method, and WAAM is increasingly being used for large-scale parts; for example, in 2017 RAMLAB collaborated with the Port of Rotterdam to produce the wonderfully-named WAAMpeller, a 180kg Class-approved nickel aluminium bronze alloy propeller made using WAAM.

In terms of materials, polymers are the most common materials for parts, particularly end-use parts. Nylon PA11 and PA12 are appreciated for their efficiency, robustness, and cost-effectiveness; the superior density and smooth finishes with 80-micron layers means that minimal post-production is required, and the technique permits up to 85% powder recycling, meaning it’s also perfect for short-run production and prototyping.

Due to its chemical resistance and almost negligible water absorption, polypropylene is perfectly suited for components exposed to humidity and saltwater. However, its resistance to UV is poor, meaning that PP parts function best in interior settings.

CEAD group, a Dutch large format AM company, produces boat hulls with an in-house developed high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a durable and low maintenance material able to produce maintenance-free, impact-resistant hulls on a large scale.

As mentioned previously with the case of the WAAMpeller, metals are highly used for their corrosion-resistant properties.

Composites are also growing in popularity, being used for structural parts without needing full metal strength. Carbon-fibre reinforced thermoplastics ensure an excellent strength-to weight ratio, perfect for high performance hulls and components. Glass fibre is ideal for structures that require good flexural resistance and cost effectiveness.

One of the principal challenges to further adoption is ensuring that parts are safe enough to hold up in choppy waters– 3D printed parts must meet stringent performance and safety requirements.

However, steps are being taken to increase regulatory compliance. As a case in point, last month saw the International Association of Classification Societies publish a new recommendation that meets the need for a standardised approach into integrating additively manufactured metallic parts into marine and offshore applications.

The recommendation encourages shipyards, OEMs, and vessel operators to adopt AM, paving the way for innovation in shipbuilding and offshore engineering. Additionally, maritime classification societies like DNV, ABS, and Lloyd’s Register are developing standards for AM parts.

Why is AM being used in the maritime industry?

Design optimisation and lightweighting

AM is principally valuable for the maritime industry due to its hydrodynamic and structural performance. It enables designers to completely rethink traditional marine component structures.

Using generative design and topology optimisation, parts can be redesigned to reduce weight while maintaining strength and integrity. This has a direct impact on fuel efficiency, as lighter vessels consume less energy.

This is particularly crucial for the commercial maritime industry; a more than insignificant sector given that 80% of worldwide trade takes place by sea. AM’s capacity for design means that companies can optimise the weight of their ships, thereby reducing emissions and perfecting efficiency.

Manufacturers can now print complex assemblies in one piece, minimising or maximising the weight at different points depending on the weight required on a particular piece to ideally align the metacentre. This is particularly useful for submarine production, as in the case of Kongsberg Ferrotech’s ‘Nautilus’ robot, which can carry out repairs to damaged metal structures at sea depths reaching 1500 metres.

Additionally, AM is revolutionary for functional prototyping. Hull models, propeller blades, and internal structures can all be tested, ensuring good positive and hydrodynamic efficiency before they’re brought to final production, optimising the design by minimising potential errors.

Reduced lead times and on-demand manufacturing

Long lead times have traditionally hampered ship maintenance and repair operations, especially in remote locations. Customarily, ship spares are shipped from a central warehouse to the ship’s next port, yet a host of problems, from shipping to the wrong port to the wrong parts arriving, mean that the process can be inefficient.

Similarly, the costs of the process can balloon once customs fees, delivery delays, and the price of warehousing and shipping parts is taken into account. With AM, companies can produce replacement parts on-site or near the point of need, dramatically shortening downtime and reducing inventory requirements.

High production speeds and a reduced workload means that parts can be prototyped or produced quicker, slashing lead times. Maritime service providers are also digitising their spare parts libraries, allowing vessels to carry digital inventories instead of physical ones. In the event of a breakdown, parts can be printed on demand either onboard or at the nearest port equipped with 3D printing capabilities.

Lower material waste and circular economy

AM aligns well with circular economy principles. Materials can be recycled more easily, and parts can be repaired or upgraded rather than replaced entirely. With current processes, the waste that replacing equipment incurs when spare parts are no longer available is significant.

3D printing is additive, so material is only used where necessary, significantly reducing scrap compared to subtractive manufacturing processes like milling or casting. Parts designed for AM don’t need the heavy scantlings of cast parts, so they use less material than injection-moulded ones. Likewise, waste from failed prints or supports can be recycled into new filament or pellets to reuse, creating a completely circular economy.

This not only lowers material costs but also supports sustainability goals—an increasingly important concern in the shipping industry. For example, the Green Ship of the Future Consortium, funded by the Danish Maritime Fund, is an independent non-profit organisation striving to ensure emission-free maritime transport with new technologies and innovation.

Customisation and complexity

AM allows for complex geometries and custom one-off parts without the high costs typically associated with tool-making or reconfiguring production lines. This is especially useful in the maritime sector, where vessels often require specialised parts tailored to specific operational needs.

Similarly, in the commercial industry, manufacturers can meet customer demand with an ease previously too difficult to achieve– bespoke parts such as cabin interiors, seats, control panels, and decorations are all possible.

Additionally, 3D printing means that the production of entire vessels is now plausible. As a case study, take CEAD’s Maritime Application Centre, a dedicated facility for both the development and manufacturing of 3D printed boats. Utilising a 12 metre robotic printer, they are able to print boats up to 12m x 4m x 2m in under 50 hours, with little to no labour costs.

Developments like these demonstrate how AM is completely revolutionising maritime production, making possible more customised, complex, and larger components.

Offshore printing

Furthermore, the ability to print components at sea or in coastal hubs reduces the need for extensive transportation, cutting carbon emissions, speeding up lead times, and drastically cutting costs.

Ships can carry 3D printers on board and produce small replacement parts like impellers, valves, and pipe fittings on board– they can even be useful for printing medical devices and prostheses for injured soldiers on board military vessels. Since 2022, several warships, including submarines and aircraft carriers, have been equipped with their own 3D printers, cutting out the need for them to go to port for potential repairs.

In June 2023, the US Navy's USS Bataan suffered a faulty air compressor, and solving this issue would have normally taken up to a year and cost up to $400,000. However, the vessel had 3D printers on board, and a replacement part was swiftly produced and implemented without the need to return to port.

Current applications and innovations

3D printing in the maritime industry spans private, commercial, and military applications and is used for prototyping, tooling, and end-use parts. The technology permits ducting, enclosures, camera casing, brackets, exterior trim, wiring loom guides, composite tooling.

Numerous companies and research institutions are pushing the boundaries of AM in the maritime space, here are a few:

Recycled surfboards

Maritime applications extend beyond vessels. Paradoxal Surfboards, spearheaded by Jérémy Lucas, is a project that uses stranded seaweed as a substitute for petroleum-based materials commonly used in traditional surfboard manufacturing around the world.

These conventional methods typically use polystyrene or polyurethane, which are toxic for the environment, energy-intensive to produce, and generate micro-plastic. This project attempts to improve surfing’s carbon footprint, fostering a circular economy in surfboard production whilst encouraging tourism in Brittany.

Aquatic drone

Royal3D, a Dutch 3D printing service provider, have recently introduced the ShearWater Aquatic Drone, a new prototype designed to tackle challenges in maritime and heavy-duty applications.

The ShearWater is made entirely from recycled and recyclable materials, and was developed for maintenance and surveillance tasks in demanding marine environments. The drone is formed of thermoplastic polymers and PETG fibre-reinforced materials, providing strength, stiffness, and impact resistance while remaining lightweight and watertight.

Completely 3D printed boats

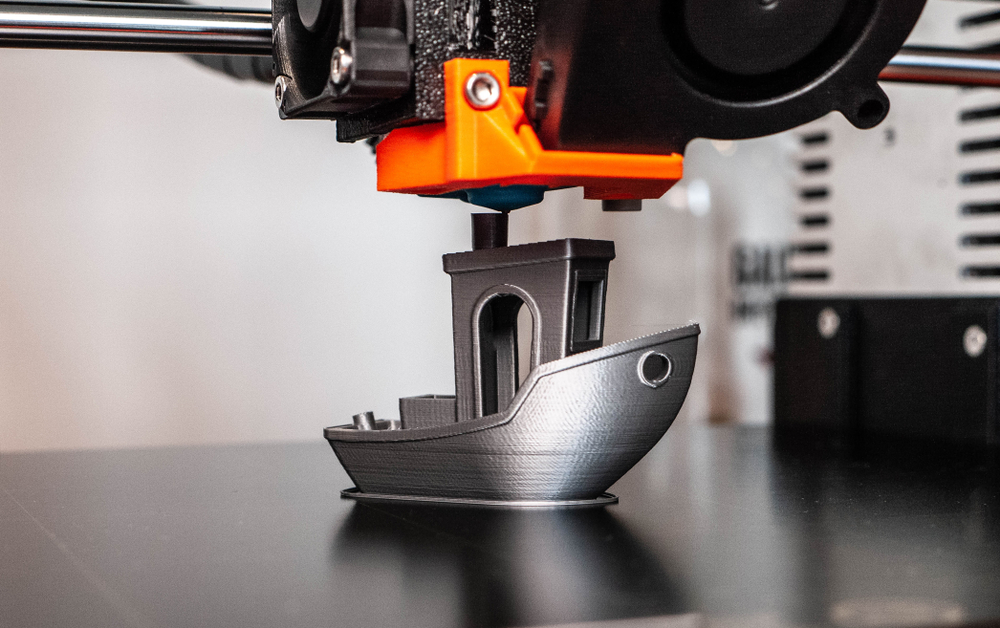

The 3D printed water taxi. Image courtesy of Al Seer Marine

In November 2023, Al Seer Marine and Abu Dhabi Maritime unveiled a groundbreaking 3D-printed water taxi, notable for being the largest 3D printed boat ever. The vessel, which measures 11.98m in length, secured the Guinness World Record for the world’s largest additively manufactured vessel.

It stole the crown from UMaine’s 3Dirigo, a 25-foot, 5000 lb Navy patrol vessel using the world’s largest 3D printer. Following this feat, they produced a patrol boat for the US Marines, purportedly twice the size of the 3Dirigo. Accomplishments like these signal the groundbreaking potential that AM possesses to revolutionise maritime manufacturing on a large scale.

The future of maritime AM

As technology matures, additive manufacturing will likely become a standard tool in the maritime industry’s arsenal. Hybrid manufacturing systems that combine additive and subtractive techniques are becoming more common, offering increased flexibility and precision. Meanwhile, AI and machine learning are enhancing design capabilities and print quality, pushing the boundaries of what's possible.

Sustainability pressures, digital transformation, and the need for operational agility are converging to make AM not just a novel option but a strategic necessity in modern shipbuilding and maritime operations.

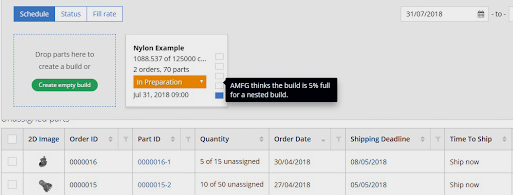

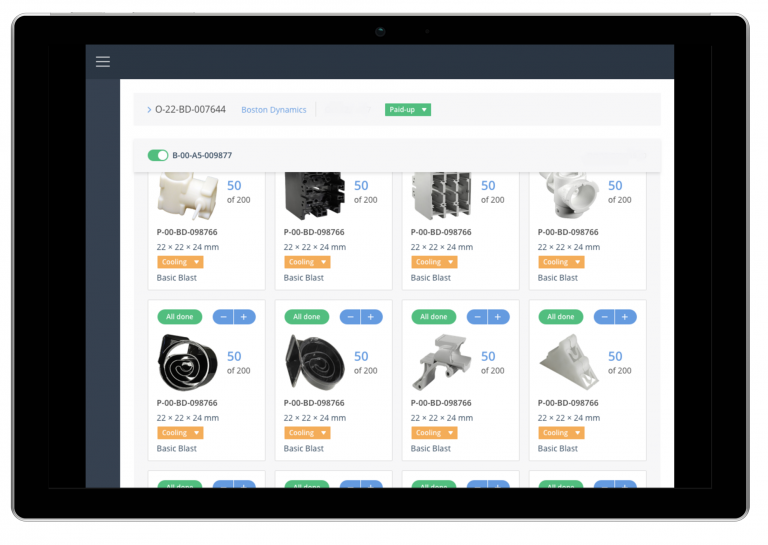

The shift towards AM adoption in discrete manufacturing is of consequential importance. AMFG supports companies across all verticals, from maritime to automotive, aerospace to medical.

Our software solutions empower manufacturers, allowing them to manage their workflows and achieve streamlined, automated processes.

With over 500 successful implementations in 35 countries and across a range of industries, we specialise in enabling companies to successfully integrate our software for AM and CNC production, into their wider manufacturing processes and scale their AM operations.

Have a chat to one of our experts here:

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)